The criticism of Parkland survivors lacks validity, creativity

In case you thought the conversation about the Parkland Valentines Day shooting was over, well, let this article be your wake-up call. We’re going to be talking about this for a long, long while. This is moreover realized by the fact that the conversation is held at a much higher level than our humble newspaper, concerning politicians, policy-makers and, of course, the survivors of the shooting.

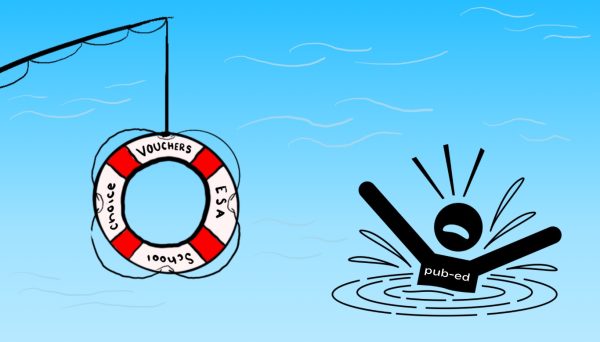

However, not all of the conversation is entirely tactful. In addition to some rather distasteful political comics which seek to undermine the activity of the survivors, there have been conspiracy theories claiming the outspoken youths are “crisis actors,” and a Florida lawmaker’s aide was recently fired for promoting such conspiracy theories.

At this crossroad we have to ask ourselves, does the youth of the speaker protect them from hate and criticism or, as active rhetoricians, do they deserve to be treated with the same callous and disrespectful language we use with anyone in the public eye?

On one hand, one has to consider the integrity of free speech. I’ve written on the topic before, but it’s worth noting once more that the right to free speech is not the right to be protected from criticism. In fact, it’s important that criticism be widely used in order to ensure there is a conversation; otherwise, we run the risk of existing in an echo chamber, never hearing the faults in our arguments, views or values.

If we wish to be able to grow and evolve in our perspectives, we will be targeted by the criticism of others. I hold this true whenever I lambast the half-brained, imbecile, nationalistic rhetoric used by the Trump administration, and I hold it true when someone takes issue with my article. In putting our thoughts and opinions out into the world, we open ourselves up for targeting. Anyone who has ever made a bad youtube video can attest to that.

That being said, not all criticism is productive or even valid, for that matter. This becomes a continuous issue for marginalized people especially, in that when they try to talk about their marginalization or experiences, they are often mistreated, dismissed or outright abused by people who don’t want to hear them. This is not criticism, this is oppression. While making observations about rhetorical devices, language, media, editing, dress, etc., may have some level of merit, we have to be able to think critically about criticism. Where is our critique coming from? Is it from a nuanced and complex view of the argument or are we allowing our prejudice to get in the way?

While the Parkland survivors are worthy of critique (I think their volume and activism has earned them that much), maybe we can try to be a little more tasteful. That’s just my critique of the critique.