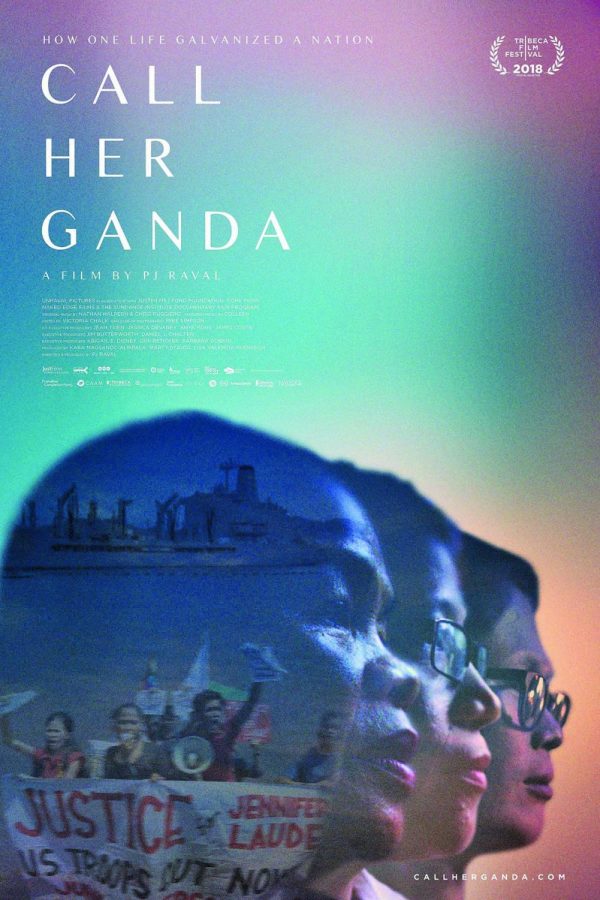

‘Call Her Ganda’ disrupts narrative between ‘developing’ countries, LGBTQ community

The film played at the Tribeca Film Festival in April.

Few directors tell the audience not to enjoy their film before the big premiere.

“I don’t think we should enjoy it,” said director PJ Raval to aGLIFF’s opening night crowd at his documentary’s Southwest premiere. “I hope you’ll appreciate it.”

It makes sense, knowing that “Call Her Ganda” chronicles the murder of trans Filipina Jennifer Laude by U.S. Marine Joseph Scott Pemberton. However, before even beginning this project, Raval told Hilltop Views in an exclusive interview that he knew this case would be much larger than itself.

“As soon as you say U.S. Marine in foreign land already that sets off a lot of red flags,” Raval said. “You can’t help but think about military aggression and you can’t help but think about the U.S. as a foreign superpower using its military aggression.”

This film goes deeper than the tragedy of this single hate crime, opting to investigate the intersection of transphobia, poverty and U.S. imperialism.

And sitting at the center of these unfolding issues is Jennifer Laude and Joseph Scott Pemberton, epitomizing the communities they stand for. Where she is a symbol for Filipino community and trans pride, he embodies imperialism, transphobia and a self-proclaimed superiority that is so recognizably American. Together, their relationship perfectly and tragically mirrors the abusive relationship of their two nations, one marred by poverty and continuous abuses, yet nonetheless struck by economic dependency.

Beyond its main purpose of telling this story, “Call Her Ganda” seeks to create discomfort: disrupting simple narratives and forcing the audience to sit in nuances, challenging our assumptions about “developing” countries and the LGBTQ community and revealing the untold history of the United States in the Philippines.

One such complexity is apparent when local Filipino vendors express their lost income because American soldiers are no longer around. Some express indifference at Pemberton’s conviction because they must make a living, even if it comes at the expense of serving American Marines.

This contradicts the united Filipino front that the audience had seen so far, a grassroots front that had been seen organizing and protesting together for Jennifer and for their country’s sovereignty. It shows the depth of dependency that the Filipino economy has built upon U.S. dollars.

Another narrative disrupting moment was during the trial when Pemberton’s sister was revealed to be a lesbian. If it is so true, Raval said, it defies the idea of perpetrators of LGBTQ hate crimes being ignorant of the community and even further to know that in a community of multiple identities, there’s not one broad stroke of homogenous understanding.

Even Raval’s intentional choices of camera equipment furthered his challenging Western ethnocentrism, he told Hilltop Views. Raval wouldn’t settle for the low production value commonly used to film countries deemed inferior. He demanded the most expensive equipment.

“Right away, I said let’s choose an aesthetic approach that really is quite cinematic and striking, let’s use equipment that is sophisticated and expensive because these people deserve it,” said Raval. “There’s a certain beauty to the Philippines and to the Filipino people that I really wanted to capture that way.”

Within all of the complexity though, there does exist one simple, irrefutable narrative: the unconditional, resilient love Jennifer’s mother, Nanay, has for her daughter. More than just a refusal to think differently of her daughter after coming out as trans, Nanay’s unconditional love led her to take on the voice of a movement.

And that, Raval believes, is representative, not an exception; the Filipino community is strongly supportive of the LGBTQ community, against popular belief that “developing” countries must be more homophobic and transphobic. And amongst this, we remember Pemberton, the convicted killer, is from “the greatest country in the world.”

The most powerful scenes engraved in my mind were always Nanay, standing with the support of Filipino activists, of the LGBTQ community and allies, speaking out for her daughter, for the greater trans community and for the Filipino nation.

“If someone like Nanay, who is not fully educated, who is coming from a poor area,” said Raval in a Q&A after the movie, “if she can figure out her political voice and use it for change, then everyone else should be able to follow suit.”

The film ends at a standstill while Pemberton appeals his conviction, a lengthy process that Raval explains is likely to find loopholes that will allow Pemberton to return to the U.S. and walk free. The audience is suddenly aware of themselves in the same time period of these events.

Now, a short five months after being finished, Raval has been rushing his documentary around the world. Debuting at the Tribeca Film Festival in April, the film has already been screened at 11 different events and four different countries, and is headed to theaters, thanks to a deal with Breaking Glass Pictures. It’s more than just the usual eagerness to get his finished work out there; it’s an urgency to affect change.

“The faster I can get this film out there, the more it can enter discussions, and maybe these discussions can influence the outcome,” said Raval. “For the film to be in the middle of the storyline, I’m hoping people will watch this film and be inspired.”

I am Lilli Hime—English Writing and Rhetoric major and freelance writer at Hilltop Views. This is my senior year at St. Edward's University.

My role...