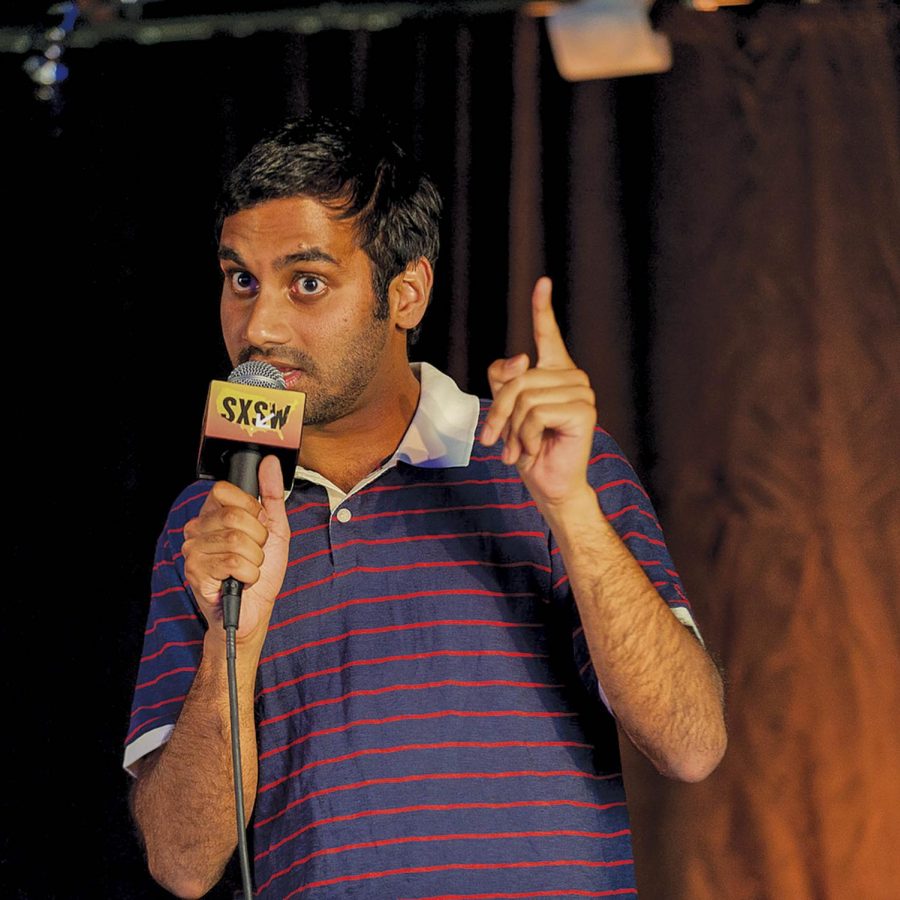

Aziz Ansari in Austin: don’t forgive if he’s willing to forget

Ansari received a lot of backlash after the initial event.

Aziz Ansari is coming to Austin Nov. 7 to warn the people of the liberal blueberry in the tomato soup of “extreme wokeness.” Strange enough, this isn’t the headline to an Onion article.

His arrival in Austin dredges up possibly the ugliest, most controversial cases during the #MeToo movement, marking a split in supporters and inciting a nation-wide conversation about what we define as sexual assault versus, as some put it, “just a bad date.”

Now, questions amount about whether he was ever guilty enough to be publicly ostracized like, what does reintegration to society look like for those accused by the movement and has Ansari’s self-determined social exile of eight months been enough for us to forgive him?

The problem with social exile is it assumes Ansari can disappear for a prescribed amount of time, long enough for the public to simmer down, and then re-emerge as if nothing happened. That’s like stitching up a wound before cleaning it.

Now Ansari can’t take full credit for this less-than-adept approach. He’s just following the playbook for any accused celebrity. Issue a public apology, usually brief, uninspiring and press-release-esque. Go into career hibernation for as long as it takes for people to forget. Re-emerge a few months later the hero whose talents our society has been lost without, who deserves a standing ovation even after numerous women have accused you.

This paradigm for how the accused redeem themselves is inherently flawed because it leaves out a crucial part: redemption. Redemption requires a longer process of learning and understanding the problem, implicating oneself as part of it and then working to stop it. It also comes through forgiving oneself and then seeking it from others in a way that demonstrates that growth.

I propose a new paradigm, one that allows the accused to re-enter society in a way that doesn’t “forgive and forget” but reconciles what’s happened. I propose the accused go against what every PR manager and every agent will advise them and, rather than never mention the movement again, open up a dialogue about it and their part in it.

And this is not to give a platform to sympathy or how they’ve been “victimized” by the movement; unfortunately many already do that in their so called apologies. This is a chance to explore the role that redeemed perpetrators can play; how they can become educated about the issue of sexual violence and actively work to not only stop contributing to it, but to prevent it and how they can address other perpetrators and ask them to change.

Consider the praise It’s On Us has gotten for the Men’s Initiative, creating a space for men, who are exponentially more likely to perpetrate, to discuss how they are part of this issue and how they can help end it. Consider this article, where a man recognizes he almost sexually assault his partner inadvertently, then works to recognize toxic masculinity in himself and engages other men in his life to do the same.

And Ansari can lead this for accused celebrities. His case was a grey area, a place open for discussion where many who were usually dichotomously split could see eye-to-eye a little better because of the case’s complexity. He can be a middle ground. He can show that even after accusations, a person can be a constructive force in the movement to end sexual assault.

So, if Ansari still “supports the movement,” as he claimed in his apology, if he truly believes that Times Up for sexual violence, as he wore that pin at the Golden Globes, then he needs to do what others haven’t. He needs to talk about it.

I am Lilli Hime—English Writing and Rhetoric major and freelance writer at Hilltop Views. This is my senior year at St. Edward's University.

My role...