Cocteau Twin’s 30-year-old album set the landscape for modern dream pop

‘Heavan or Las Vegas’ is the sixth studio album by the Cocteau Twins. It became the band’s most successful release.

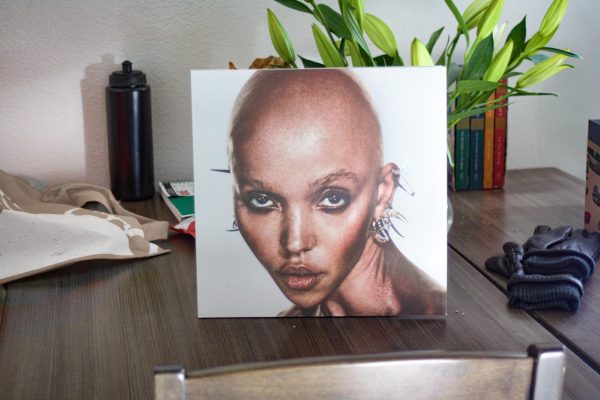

Album art serves as a visual vessel for the auditory content of an album. No album art serves this purpose nearly as well as Paul West and Andy Ramball’s cover for Cocteau Twins’ 1990 album “Heaven or Las Vegas.” In the words of the photographers, they were making an attempt at “captur[ing] the ethereal” that Elizabeth Fraser, Robin Guthrie and Simon Raymonde so effortlessly demonstrate on the album.

“Heaven or Las Vegas” turns 30 on Sept. 17, and with 30 years behind it, the album still stands as the blueprint for all modern dream pop. Quite fittingly in line with the moniker of dream pop, the title of the album creates a dichotomy: true bliss or just a false imitation; and the content delivers on the outright existential themes of the title.

Written amidst and after the pregnancy of lead singer Fraser, “Heaven or Las Vegas” contains the band’s most affecting and, frankly, intelligible lyrics of their career. Unsure of her songwriting ability, Fraser had mostly slurred and improvised the language of the band’s eight year career.

Still, the vocals of “Heaven or Las Vegas” are heavily coated in an otherworldly combination of effects that grant them an alien feeling, but this time they hold real world English meaning about death and the serious gamble of bringing life into the world. The vocals are something both relatable and nearly completely abstract.

Opening with the ubiquitous indie-steamy-car-makeout-session track “Cherry-Couloured Funk,” listeners are instantly steeped within the cannabinoid-like bliss of the album. The track describes the problems that every relationship faces with Fraser singing, “Bills and aches and blues / And poor little everything else / But still more unstable, eyes of glass / Not get pissed off through my burned lips / As good news.”

While sexy and ethereal, much of the record is concerned with relationships, but not just romantic ones. “Pitch the Baby” is about Fraser’s delivery of her and Guthrie’s child while “Frou-frou Foxes in Midsummer Fires” was written the day after Guthrie’s father passed away. Part of the album’s strength relies on its ability to deal with these sorts of themes while retaining its separation from a certain musical material reality.

The title track of the album displays the central idea of the record: is this relationship something good or am I lying to myself? Again, the dissociative quality of the instrumental aspect of the album allows for listeners to lose themselves within this thought.

Hi! I'm Ben Cardillo, I will be graduating this May with a major in Writing and Rhetoric and a minor in Photography. I grew up in Tampa, FL (go Bucs),...

Ouime • Oct 23, 2020 at 8:15 am

It was Simon (bass player) who’s father died while recording Heaven or Las Vegas. The song was started by Simon (on piano) and Robin (Guthrie) then added his ideas to it before Elizabeth put the vocals and beautiful melody on the track and called it “Frou-frou Foxes in Midsummer Fires”