Lost in translation: First Amendment fails to conserve integrity of student press organizations

For a generation with such a fervent value of “freedom of expression,” we don’t really understand what that means.

After a student photographer was harassed and denied access to a public protest at the University of Missouri on Monday, the routine review of that worn out First Amendment right has been tirelessly written about and discussed by the media, and with good reason.

The student photojournalist on the scene, Tim Tai, was pushed, taunted and blocked from completing his assignment by not only a group of students, but faculty as well, on the grounds that the protesters’ campsite was a “safe space” free of the media.

Ironically, Professor Melissa Click, who was temporarily associated with the university’s school of journalism until her resignation Tuesday, according to The New York Times, was among the protesters urging Tai to leave and even calling for “some muscle” to remove him.

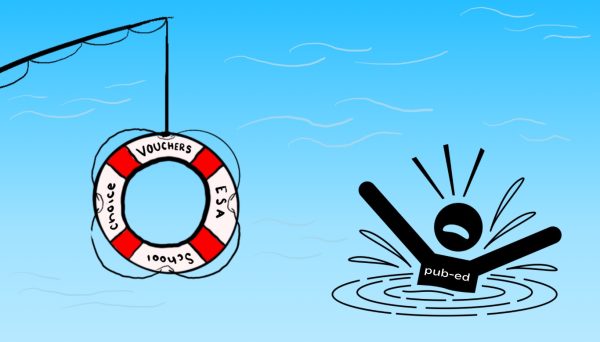

Everyone seems to want freedom and equality until it is an inconvenience to them or their own cause; the very same right that was protecting the student protesters at Missouri should have also extended to the student documenting their actions, but it unfortunately failed him.

Apparently, the portion of our population that feels most entitled to demonstrate and shout is also the most sensitive. They march out on campus lawns and protest, and then paradoxically recoil when they feel their “safe space,” (whatever that is) has been “threatened” by the scary student media.

When a single student journalist with a camera is deemed more offensive than a mob of student protesters, there is a problem. When professors and faculty support and encourage this behavior, there is a larger problem.

Although Click apologized and withdrew her “courtesy appointment” from the university’s journalism school, it is still confounding that her initial reaction to the situation was to call for “some muscle” to remove the obviously passive documenter.

As a part, albeit a very minuscule one, of Missouri’s journalism school, she should have recognized journalists’ right to be at the scene. As a professor, she should have realized that joining an entire mob against one student rather than quietly assuaging the situation was a bad idea.

But Click’s bad judgment Monday is reflective of a not uncommon attitude toward student journalist. Her actions represent a much larger national problem afflicting student press on college campuses. The barely-valid anxiety produced by student media (and almost anything else concerned parents and university staff have had the opportunity to vilify) has been blown up, and way out of proportion.

Although the general fear of student journalists might be justified — their tendencies to misrepresent facts, mix up numbers, probe controversial topics and uncover information makes them understandably terrifying — the amount of censorship imposed on them is entirely unreasonable.

Even at St. Edward’s University, a small, cozy, community-based liberal arts institution with seemingly little to hide, student journalists are routinely denied comment, asked to leave events and even yelled at over trivial mistakes.

Student press organizations function to provide students with a variety of invaluable skills useful in all aspects of life; professionally, personally, socially — even spiritually, if you’re doing it right. They do not exist to wrongfully expose or exploit anybody.

Whether they fail or succeed is another question, not a concern large enough to warrant maltreatment from university faculty.

At the end of the day, the student press remains transparent: when we mess up, we issue corrections, and no one (at least in the history of this school) is hurt.

At the end of the day, who’s afraid of the little, curious student journalist, anyway?