New law requires private universities to disclose police reports

As the national spotlight on campus safety has intensified in recent months, Texas joined five other states in making police department reports on private campuses subject to public records laws.

Senate Bill 308 became effective Sept. 1 and brought Texas in line with Connecticut, Georgia, North Carolina, Ohio and Virginia in requiring police departments on private campuses to disclose the same information in officers’ incident reports as must be disclosed at any other police agency.

“A campus police department of a private institution of higher education is a law enforcement agency and a governmental body for purposes of [the open records act] only with respect to information related solely to law enforcement activities,” according to the new law, which was sponsored by state Sen. John Whitmire, D-Houston, and state Rep. Garnet Coleman, D-Houston.

What does this mean for St. Edward’s University? Hilltop Views decided to find out by making a request under the state’s public records law for all police reports involving drugs or alcohol dating back to Sept. 1, 2013.

The newspaper submitted the request on Sept. 3 and received the final records on Sept. 11. The process of obtaining the reports was new territory for both Hilltop Views and for the University Police Department.

“I think that open records is a good thing,” Police Chief Rudolph Rendon said. “It makes an agency — it makes us — transparent on how we conduct our business and how we record it.”

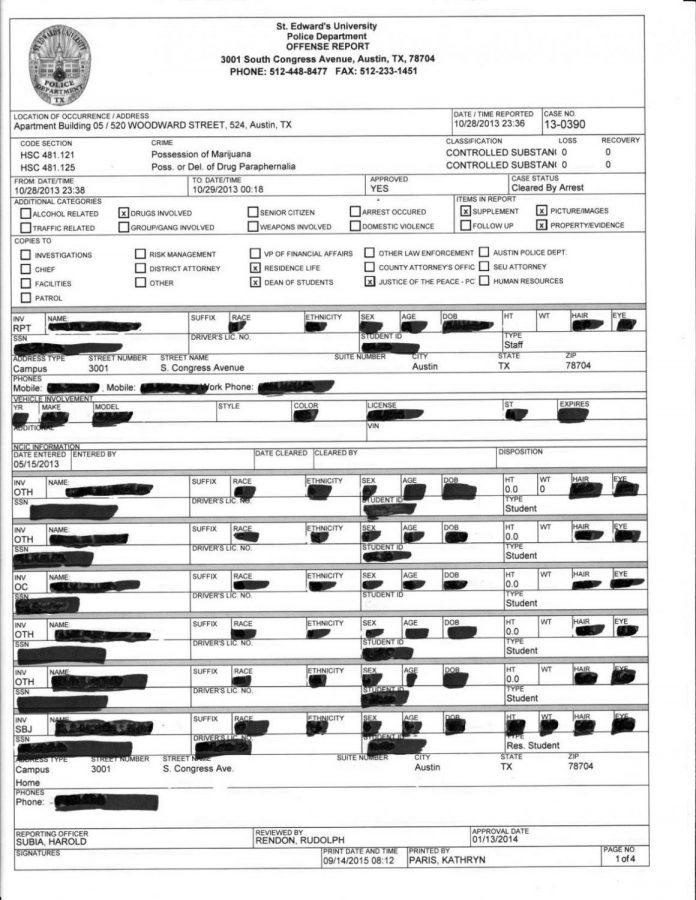

Initially, however, Rendon’s department responded to the Hilltop Views request by returning the records with so much information redacted (literally, crossed out with black ink) that it was difficult to discern much of the information included on the documents.

Rebekah Desai, director of risk services at St. Edward’s, said that because of the newness of the law “there are procedures we are still establishing to address these requests,” which is why UPD over-redacted the initial police reports.

After consulting with the university’s attorney, St. Edward’s corrected the error and provided records that are accurately redacted, Desai said.

Social Security numbers, student identification numbers, license plate information and vehicle information numbers were the only items redacted on the new police reports.

A records request is not free. Hilltop Views was billed $96.55 for 5.26 hours of work, Office Specialist Kathryn Paris said in an email on Sept. 18. This is the charge for the first 15 reports, that were redacted. Hilltop Views is waiting for a final total.

“It can be costly, plus it takes time for my clerk to actually reproduce those files and to redact them and all that kind of stuff,” Rendon said.

FERPA

The Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act is a 1974 federal law that protects the privacy of student education records. Education records includes records, files and documents which contain information directly relating to a student that are maintained by an educational institution, agency or person acting for the institution, according to the United States Department of Education.

Police reports are not covered under FERPA. In fact, police reports are one of four categories of records that are excluded from the act, according to the U.S. Department of Education. In 1992, Congress amended the law enforcement exception so that the exclusion applies to “records maintained by a law enforcement unit of the educational agency or institution that were created by that law enforcement unit for the purpose of law enforcement.”

Police reports and students

Under this new law, only very sensitive information will be redacted from police reports including Social Security numbers, student identification numbers, license plate information and vehicle information numbers.

With this new law, names of students who reported, witnessed or were suspects in incidents are now public record. Victoria Godinez, who was the front desk worker at East Hall, reported an incident involving marijuana in East Hall on Nov. 13, 2013, according to the police report. The responding officer was Alice Gilroy.

Godinez does not have an issue with her name and information being available for anyone who requests it, but is concerned that it could deter others.

“I guess for other students that might have been involved, they might be kind of hesitant to have their information out there knowing ‘Oh yeah, I’m the person that told on you,’” Godinez said.